First off, video games are expensive art forms. The amount of money it takes to design, program, produce, and get a game successfully onto the marketplace is a figure with a lot of zeros. To put it into perspective on just how much our favorite games cost to make, Skyrim topped out at $100 million, Final Fantasy VII was $145 million and Grand Theft Auto V’s price tag was $265 million. Now, these are all AAA games that well-established companies produced and small developer indie games don’t require nearly as much cash to make, although they often take longer to develop.

Hit games like Skyrim and GTA can have pretty big payoffs, and put a lot of money back into the companies pockets, but what about indie developers who couldn’t get away with charging the same prices as, let’s say, EA? This was the birth of a new business model, when gamers were introduced to what is called “in-game purchases.” These seemingly harmless transactions can be found in nearly every game on the market now, and allow players to pay small amounts of money in exchange for more in-game currency, assets or special items. We see a lot of these on mobile apps such as Clash of Clans, or Facebook’s Farmville. Since 2010, in-game purchases have become a common thing for games and have been another way for developers to make more money, months or even years after their game’s initial release.

In-game purchases also allow mobile app developers, in particular, to charge significantly less for their games in order to make them more appealing. PC and console games run for anywhere between $30-60, but a game on your smartphone is only a couple bucks, and sometimes completely free to download. But how do you make money off of a free game? Most consumers are hesitant to pay for a game on the app store unless there is considerable hype and plenty of good reviews to back it up. However, free downloadable games are a different story. Consumers may have had the intention of only playing the free version, with the attitude “I am definitely not wasting money on this, what silly person would pay $49.99 for a sack of gems?”

You may come to the conclusion that there are a lot of silly people in the world when a game like Clash of Clans brings in 2.3 billion dollars in 2016 (Intelligent Economist).

The fact is, games depreciate like cars. Upon release, most games can be sold for around $60, and within a few months after the initial hype has died, tend to be available for $39.99. By the following year, the same game will most likely appear in the “Hot Deals” section of the marketplace. With the exception of a select few titles, developers really only have a few months to make fortune before a game becomes old news, and they are fully aware of this. So what do they do to keep the money flowin’? Let’s ask our good friends over at EA.

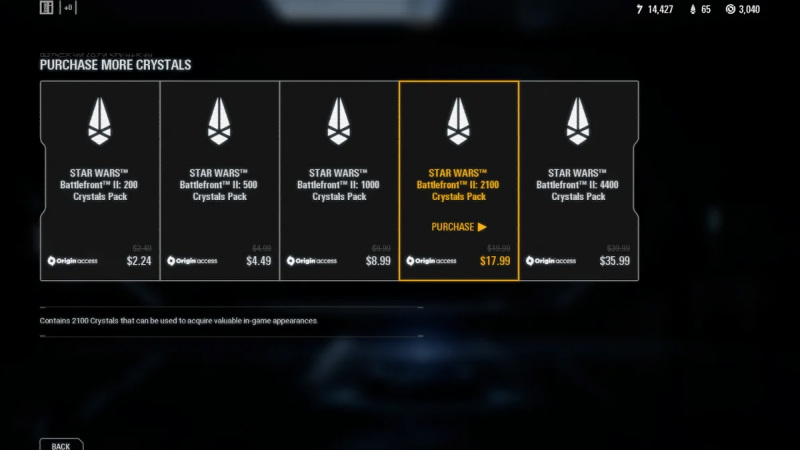

To start, EA currently has 26 games in the FIFA series, a franchise that has become a reliable cash cow for the company. Sure, the graphics improve year after year, and the roster is updated, but in reality FIFA is basically the same game each year. So how does it account for nearly 40% on EA’s annual revenue? The answer is the Ultimate Team Feature, a microtransaction that is here to stay. Basically, players can pay money to have football icons on their team, and play against opponents from around the world to earn weekly rewards that will potentially make their team better. A more famous example of microtransactions hit the market in 2017, when Star Wars Battlefront II came out.

This game was the first to really give microtransactions a bad reputation, and created a lot of controversy over whether purchases of this nature are ruining what makes video games so fun. Normally, microtransactions are linked to an in-game credit that is awarded based on individual player performance. The better you do during a match determines your rewards upon completion. This motivates gamers to play more in order to up their skills, earn better rewards, and use said rewards to forge a better character/team. With Battlefront II, EA chose to award the same number of credit to every player at the end of a match, no matter how well each player performed. With the earned credits, players were given an opportunity to spend them on RNG loot boxes or locked content. With a loot box, normal progression was thrown out the window. An item that ordinarily would have unlocked with accumulating earned experience (XP) could now be bought with credits, or in-game currency purchased with real money. To top it all off, a loot crate doesn’t always provide valuable items either. This is when microtransactions become cynical.

With the help of a random number generator, a player uses credits in exchange for a ‘loot box,’ an animated crate that generates a handful of often useless items, with rare items of much greater value occasionally, and at random, being generated. There are two major things wrong with the system:

Firstly, if players are able to purchase boxes that possibly contain items that will allow them to perform better in games, what is the point earned skill? This option eliminates the value of accomplishment, and grants experience to those who have the means to purchase loot boxes. This, sadly, defeats the purpose of strategic, battle-oriented video games that aim to foster a sense of teamwork, skillfulness and ultimately fun entertainment. I mean, why even bother learning to excel at playing a certain game when your opponents can easily purchase prowess.

Secondly, and more towards why EA received so much scrutiny over this decision, is that purchasing loot boxes could be seen as a form of gambling. In general, a loot box only costs a few dollars and appears harmless when players weigh the rewards. Spending $2.99 for the chance at obtaining a legendary weapon that will substantially increase your likelihood at winning match after match? What’s the worst that could happen?

A $90 credit card charge a half hour later and an inventory full of useless weapons, that’s what.

You see, not every box contains a valuable item, and in reality you won’t be seeing such an item in the next 5, even 10 boxes you purchase for $2.99 a piece. Unfortunately the 11-year-old kid with their parents credit card information is probably thinking that the next box might be a winner, and is enticed to buy box after box until they are eventually graced by an innocent, random generator.

Now, EA did get in trouble for this, although it hasn’t really stopped them, and developers, from continuing to implement some sort of microtransaction business model into their other games. It’s not an unrealistic assumption that every industry is willing to make some sacrifices if it means they will turn a greater profit, and the gaming industry is no exception. Unfortunately, it appears that these methods, such as the use of microtransactions, imply losing sight of what makes video games one of the most enjoyable art forms in existence.