Earlier this year, I interviewed monster artist Rachel Briggs, who created the Ken Sugimori style art inspired by unused Pokémon featured in the Spaceworld 1997 Pokémon Gold demo and also contributed a few monster designs to upcoming title Monster Crown. I knew she was a big fan of Keitai Denjuu Telefang, a series of Japan-exclusive monster RPGs for the Game Boy Color and Game Boy Advance, but I had no idea she had been helping with the creation of an English fan translation of the first game or that some of individuals from Team Spaceworld came from the online Tulunk community. I spoke with several of these individuals including Rachel herself once again, Samuel “obskyr” Messner, Sanqui, Andwhyisit, and Kmeisthax, to find out more about their knowledge of Telefang, the various quality of English translations and the difficulties of trying to create one, video game preservation, and upcoming mongames — a common term used for monster taming games by fan communities.

Secret Pokémon Games, Pokémon Ripoffs, or Something More?

Secret Pokémon Games, Pokémon Ripoffs, or Something More?

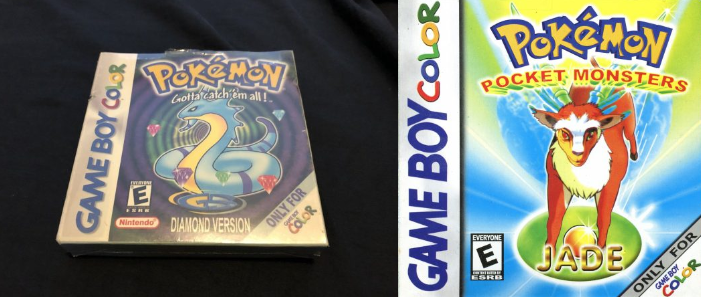

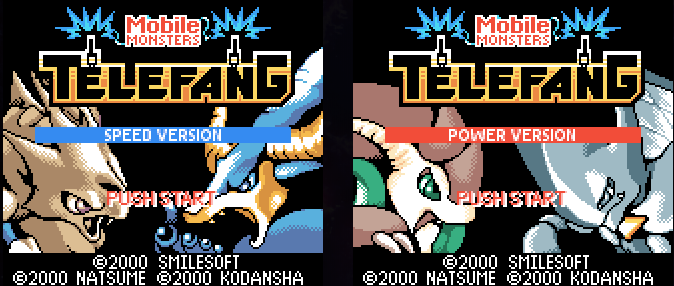

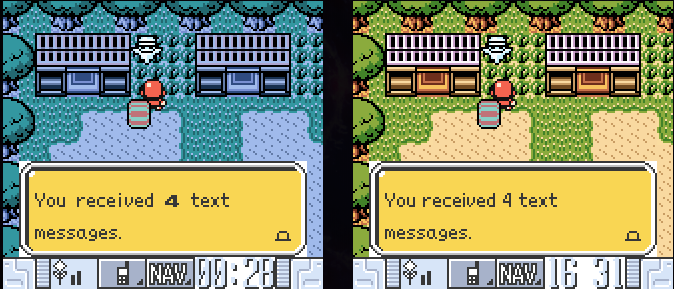

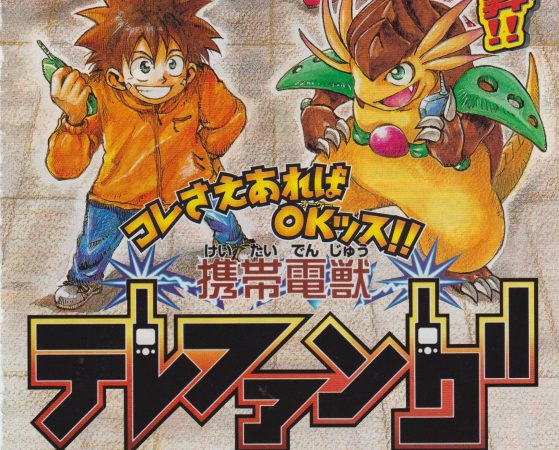

Keitai Denjuu Telefang, which translates to Mobile Phone Beast Telefang and is usually shortened to just Telefang, was developed by Smilesoft, with the first game launching on November 3, 2000, with two separate versions, Power and Speed. Sometime later, bootleg versions of the game titled Pokémon Diamond and Jade were found, which is how it is best known by English speaking audiences.

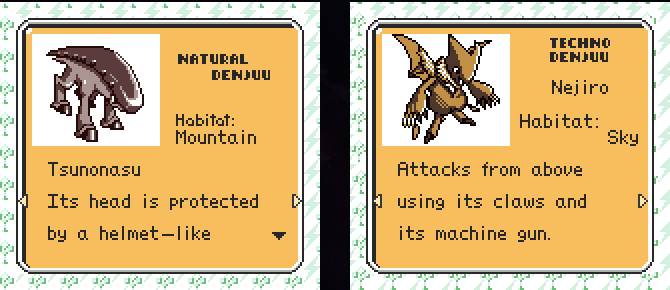

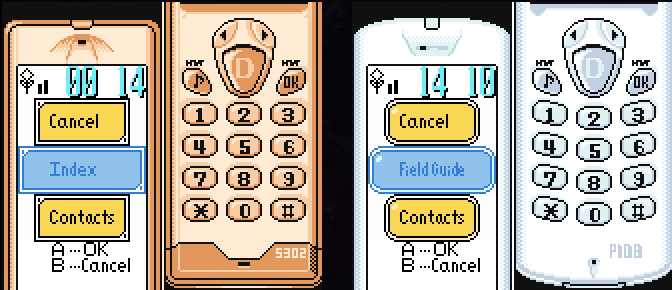

In fact, these bootlegs are typically how the English fan translation team found out about the games.“I first discovered Telefang through the bootleg games Pokémon Diamond and Jade, like many people of my age.” says Sanqui, “As a kid I would go on the internet and download ROMs from a Czech Pokémon fansite. The bootleg Pokémon Diamond was available there among other legitimate and illegitimate titles.” While some thought maybe this was an unreleased Pokémon game when first found, others easily recognized the difference and saw how it stood out among its sole competitor, which is what it was like for Andwhyisit, “I realized one day that there was a real game underneath the Pokémon Diamond bootleg. The idea of exchanging numbers with monsters to call them into battle was such a fun concept, and unlike Pokémon‘s ‘Will I? Won’t I?’ about battling with multiple monsters at once Telefang fully embraced that mechanic from day 1. The world itself was memorable too. Unlike Pokémon where monsters are glorified pets, Denjuu (the name of the monsters in Telefang) are as intelligent as humans and have their own society.”

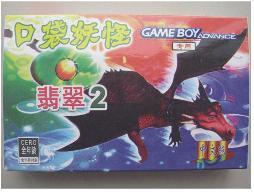

Kmeisthax provided some additional information about the specific bootlegs in question, “The bootlegs that everyone in the west knows about are so bad because they’re actually double translations, from Japanese to Chinese and then English.” But as it turns out, these often found ROMs weren’t the only Telefang bootlegs available, “there’s also a Telefang 2 bootleg with an incredibly predictable name (Pokémon Diamond 2 and Jade 2). NES bootlegs were also made of Telefang, by a company called Waixing which absolutely loves to make top-down NES RPG demakes of every mongame ever. Aside from Waixing, we don’t know who made the Game Boy bootlegs, nor if they were even a single entity or multiple bootleg companies ripping each other off.” While either case could be likely, it’s important to note that the art shown on the covers of the Pokémon Diamond and Jade bootlegs aren’t actually from Telefang at all, with Jade’s being a mashup of designs from Princess Mononoke and Diamond’s being a snake creature of unknown origin, both only appearing on the box art and title screen.

While these individuals found Telefang through bootlegged copies, others like Obskyr found out about Telefang through another channel, “At one point, devotedtoneurosis (developer of Monster Crown) wrote to me on Twitter about Lanette’s Time Capsule, another project of mine. We talked a bit, and based on my experience with reverse engineering and Japanese, he recommended I talk to the http://telefang.net gang. I did, and got into it from there. The main thing that drew me in was the circumstances of the translation project, actually! A well-made Japan-only monster collecting RPG, which is somewhat mythical in the West for various reasons, but has never been properly translated… It was hard to resist the chance to work on something with such a storied history, and bring something so great and so misunderstood to the masses. Then there was the community – a tight-knit gang of passionate, friendly, and knowledgeable people to work with, learn alongside, and get to know as friends.”

Through some poorly double translated bootlegs and plenty of curiosity, an entire online community came together and developed a higher quality English translation. Although we know some information about Telefang, there’s likely still more to the story. While many outside of Japan learned about Telefang through these bootlegs, what do we know about how it was received in its country of origin, and what its development was like?

Poor Popularity

No one is quite sure about the popularity or reception of the Telefang series in Japan around the time of launch, besides the fact that its sales numbers were less than stellar, and even artist Saiko Takaki, who now illustrates the Vampire Hunter D manga, doesn’t remember much about it besides recalling that it didn’t sell well enough for her to receive royalties.

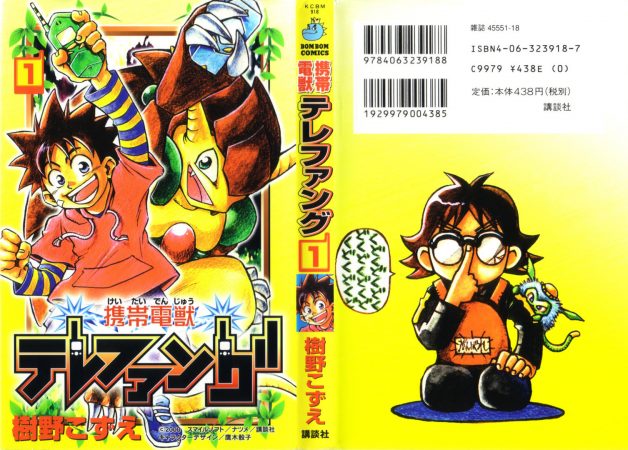

Telefang did have its own manga series prior to release, however, and Rachel had this to say, “The Telefang manga was published in Comic Bombom, which also shared some interesting prerelease information. It seems the games changed a bit during development, which is evidenced by things like Bombom‘s screenshots of prototype details, and some data left over in the final ROM. For example, it appears as if they were originally intended to be fully Game Boy Color games with Super Game Boy features, but this was scaled back to just being Game Boy Color-enhanced for release.” There’s no exact way to know if these removed features would have increased Telefang’s popularity or memorability in the long run, but it’s interesting to note they were being considered at one time.

Despite its lack of popularity, Telefang still managed to receive a sequel on the Game Boy Advance on April 26, 2002 titled Telefang 2, once again being split between Power and Speed versions and also received its own manga series in Comic BomBom, but unlike the first was never reprinted or compiled into volumes.

As mentioned previously, Telefang 2 also received its own bootleg copies (unsurprisingly) titled Pokémon Diamond 2 and Jade 2, which contained the Pokémon Arcanine and the dragon from Shrek on their box art and title screens, although these seem to be less well known than the previously bootlegs due to scarcity. “I think it speaks volumes that the game has had a vibrant dedicated English speaking fan community for ten years by now,” Sanqui says, “but we’re not aware of any over in Japan. Telefang is scantily mentioned on message boards and mostly a curiosity for those who do remember it.”, while Kmeisthax mentioned, “It (the first game) got a booth at SpaceWorld, so I imagine it got a decent amount of exposure.” For more information on the series, you can also check out Wikifang, which was also partially developed by Rachel and the rest of the team.

English Translation Difficulties

Despite its lack of popularity, Telefang was able to avoid completely fading into obscurity and has been well supported by this niche online community, with an English fan translation as the ultimate result. But making a better and more accurate translation was far from easy, and it seems that there’s much more to it than simply translating a game from one language to another. Roles had to be split between hackers and translators, due to not having access to a source code or technical information, and hackers had to do their best to reverse engineer the game so that everything could run well together.

“Perhaps the most interesting is that the Telefang translation, due to how long it’s been in the works, started as a binary patch!” Obskyr claims, “ What that means is that, rather than having source code, the hackers working on it would put machine code and data straight into the ROM and throw that around to each other. This not only meant that only one person could add things to the patch at any one time, but also that it was nigh-impossible to read and make sense of the patch code or make anything but trivial edits after the fact. Two years ago, Kmeisthax took on the year-long behemoth of a job of disassembling the patch – basically, we were reverse-engineering our own code! It took about a year, but he did it. Without him, we wouldn’t have a tolerable (and even comfortable) working environment.” The development process has clearly been a great learning experiencing for the team, with Andwhyisit adding, “When I started this patch I didn’t know much of anything, all I knew at the time was how to open the game in a hex editor or in tlp (Tile Layer Pro) and make basic edits, we were basically figuring it out as we went. Of course my plan at the time was to implement a basic menu patch so that we could navigate the menus at least, since I am no translator, but Kimbles posted a translation of the intro for the game and things snowballed from there. Eventually Sanqui and I started to learn Gameboy z80 Assembly and our horizons expanded significantly, things were going good.” Although developing an English translation proved to be a more harrowing task, it seems that the team is proud of their effort. “We have overcome many difficulties over the years,” Sanqui says, “ When we were starting out in 2007, none of us had any knowledge of how Game Boy games are coded. Following dodgy ROM hacking tutorials, we toyed with hex editors and graphics editing programs to insert English into the game, and every small advance was celebrated. With years, our skills grew and today, we have a disassembly project that allows us to understand and overhaul the game’s code painlessly.”

While learning what they had to do to reverse engineer the game took time, the actual translation of Telefang from Japanese to English was no small feat either, and came with another set of difficulties. “Telefang is a bit of a unique beast. It has hundreds of phone conversations with the monsters, all on random topics ranging from family troubles to proverbs to children’s songs.” recalls Obskyr, “These have required an immense amount of localization work – after all, ‘the child of a frog is a frog’ is nonsense to an English speaker. Coming up with equivalent English references and making similar conversation about them has been a real challenge.” Besides improving localization for an English speaking audience, one of the biggest problems the teams have encountered seems to be text length, “Japanese in general requires less characters to represent text than English does, and eight letters proved insufficient to represent the names for Denjuu.” says Sanqui,“Rather than opting for shortening the names and mangling them in the process, we went through a lot of effort to make it possible to display even long names like Ornithogalum and Arachdebaran.” Kmeisthax added, “Japanese text tends to be highly compact for grammatical reasons, and translating back into English doubles that length. This means that translated text strings won’t fit back into the ROM they came from, and they’ll overflow the space visually allocated to them on the screen.” Even with these difficulties, the team managed away around it to fix and further improve the translation, “In terms of text location in the ROM, we have been able to find a lot of free space in the ROM to put things in” Kmeisthax continued, “Moving things around in a compiled binary is difficult, but we’re lucky in that a lot of Telefang things are relocatable to begin with. Visually, we had to implement proportional font support – not only does it look a lot nicer, it also saves visual space. We actually implemented a second narrow font that’s automatically selected when a string won’t fit normally, which has actually fixed a lot of text overflow bugs. Finally, if a string just won’t fit, we’ll redesign the UI if we have to to make it fit.”

Fitting in more text was not the only problem with translation, as finding individuals interested in helping with translation was tough as well, “One of the biggest problems we have always had with this project was that we had so few translators.” Andwhyisit says, “Kimbles got occupied with life. DaVince tried to take on the mantle of translator, but he too didn’t have much time to do it, in the meantime us rom hackers were doing work on the patch, but things were slow. During this time kmeisthax started work on a partial disassembly of the rom and patch so that we could track our changes and allow us to produce patches for both versions of the game. And then Obskyr later appeared on the scene and suddenly we had a translator again. Work on the patch has been booming ever since.” Translating Telefang may have proven to be a more arduous project than originally thought, but even after the team feels like there are no further improvements to be made, there’s still more work to be done elsewhere.

Translating Telefang 2 and Other Smilesoft Properties

Although the Telefang 1 has been fully translated into English, it’s still an ongoing process with constant improvements. As for the possibility of a Telefang 2 English translation, Obskyr claims, “We’re always throwing ideas around! It’s all hypothetical, though – we all agree that we should finish Telefang first.” Kmeisthax adds, “Historically, we’ve had two different Telefang 2 projects, both of which have been abandoned. One translation project was started to create a completely new patch using the bootleg translations; while another existed to inject correct translations into the bootleg ROM. Neither project is currently maintained.”

Believe it or not, Telefang was actually not the only monster series made by Smilesoft, as they also created Network Adventure Bugsite, which according to Kmeisthax, sold worse than Telefang due to the company only releasing a limited edition, and GachaSta! Dino Device. After these two games, Smilesoft was reformed into Rocket Company, which Kmeisthax says then focusing on contract work and Japanese Kanji literacy until it was bought up by Imagineer (who also publishes the Medabots video game series) and closed down not too soon after.

As for the possibility of seeing fan translations of Bugsite and Dino Device at some point, Andwhyisit says, “There is already some work done towards Bugsite (albeit not recently), and kmeisthax has been preparing a build environment for GBA titles so we can work on Dino Device and Telefang 2. However the main focus has always been getting Telefang 1 translated first.” and Rachel adds “most of those have actually already been poked at to make English menu patches or the like, to make understanding basic gameplay a little easier. It’s just easier to work on one major translation effort at a time.” with Kmeisthax further adding, “After I had disassembled the Telefang fan translation and produced source code for it, I did the same to Bugsite in order to revive that project. However, we don’t currently have a translator for it. I’ve stepped in to translate what I can, but my Japanese knowledge is too limited to see that through to completion. I’m currently in the process of disassembling Dino Device, at the request of one of the translators. Apparently it will be a short translation job, so we plan to do that first before taking on the task of restarting the Telefang 2 project.”

“None of these games, being related to Telefang by virtue of the publisher, Smilesoft, have been forgotten, and translations projects in various stages of completion are underway.” Sanqui says, “Some of us also participate on other translation projects, such as for the Medarot (Medabots) series. The real blocker for these projects is simply time, as making a solid translation is no quick matter, and we all work in our free time.”

What Makes an English Translation Great

Due to the team’s experience with the subject, I had to ask them what do they think makes a good fan translation great and how do they walk the line between an authentic translation and an entertaining one? In response to this, Obskyr says, “As fan translators, we have the luxury of choosing our translation philosophy freely. In a commercial context, localization will often do sweeping rewrites to fit what’s expected to sell better or perceived to fit the target culture better. We, however, do our best to let the original’s humor and style shine through. To do that successfully, you need a good sense not only for the language you’re translating from, but the language you’re translating to. If you stick too close to the original script, you end up with unnatural and stilted English – ‘translationese’, as it’s called. With that in mind, when you’re putting together an idiomatic and natural translation, it’s important to be able to formulate something that reads with the flow and nuance a Japanese speaker would’ve experienced reading the original work. A truly great ‘faithful’ localization matches not the words and form of the original, but its intention and feeling.” with Andwhyisit adding “The problem with Japanese to English translations is that Japanese uses less characters to convey the same message (as mentioned earlier) and their lettering is more consistent in width. This meant that all text had half as much space than needed for English names, both on screen and in text tables. Most of your official translations in the 90s just accepted the limitations and made their names shorter. The quality of translations in the 90s suffered as a result.” For example, some older Game Boy Games such as Dragon Warrior Monsters and its sequel have only four or five spaces when entering your name, which is annoying when your name is six letters (like mine), but over time developers have found ways around this. “Things like text inserters, variable-width fonts, doubling of limits, overflow banks and more allow translators the freedom to translate text without feeling restricted by any feeling of what they can or can’t do.”

“Technical polish really helps. It’s fairly easy to take a game and produce passable translations of the menus, but you need to spend lots of time modifying game code just to produce a result that looks the part of an official translation.” says Kmeisthax “If you’ve ever loaded up a translation patch where all the text is weirdly tracked or kerned using a monospaced font, they probably didn’t do any of that work, and the user experience will suffer for it. I’m not a translator, but the rule I’d imagine one would keep to for this sort of thing would be to avoid turning the game into something it’s not. Punch-ups and dialogue rewrites are often necessary to maintain the tone of the original work, but it’s very easy to wind up changing the character of the work by accident. In a fan translation, we don’t have the ability to ask the authors how something was intended to be perceived, which adds further difficulty.” and Rachel adds “I think the most important part of a fan translation might be the ‘fan’ part, that is, it helps to have a very good understanding and appreciation of the original material to work from if you want the spirit to carry over in translation. Sticking too closely or being too literal can take away from the final product.”

No Copyright Worries Here

With companies like Nintendo cracking down on ROM sites, the team isn’t too worried about losing the work they’ve put in, since Telefang and other Smilesoft properties are in a legal limbo of their own, with obskyr stating, “Fan translations have a history of being allowed to flourish, and… let’s just say that Telefang isn’t at the top of the list of harshly protected IPs. If we were to be targeted, no – it’ll never be in vain. For one, a fan translation project like this is a matter of personal growth for all involved, which can’t be taken from anyone. The work we’ve done wouldn’t disappear either: the nice thing about the internet is that once it’s out there, it’s out there.”, while Kmeist added, “having your fan project killed because some lawyer decided to take potshots at it will never ever feel okay.” and, “That being said, the likelihood of this is surprisingly low. There’s precisely two reasons why a ROM site gets taken down: It’s a licensed game, or it’s a Nintendo game. Most companies approach copyright and trademark enforcement for the purposes of reducing piracy of the products they are currently selling. Nobody at EA cares if you’re pirating their old DOS games, since they have no market value to begin with.” later clarifying that, “Telefang as a franchise no longer exists. Smilesoft no longer exists. It’s part of Imagineer now. They do contract work for other publishers and don’t own any of their own properties. So there’s absolutely nobody actually engaged in enforcement right now.” “I think they prefer to focus their takedown sweeps on fan games or hacks of popular series, especially those with imminent releases.” Rachel adds, “Regardless, if we ever had to cease work on the translation project for any reason, we still have built a fantastically skilled tight-knit community.”

The Future of English Fan Translations

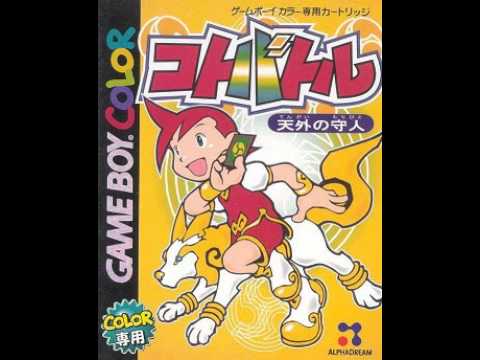

While there are a handful of English fan translations of many video games available or in development, there are always more to cover, particularly regarding older games that have no chance to be officially localized, as for English translations the Telefang team would like to see in the future, whether official or fan made, there are plenty, One of my dream translation projects is Kotobattle (seen above), the Japan-only GBC pseudo-mongame RPG where you battle using kanji.” says Obskyr, “It was the first game by Alphadream, who went on to develop the Mario & Luigi series. I have no idea how I’d make it work in English, but I do love a challenge.”

“One curiosity I always remember is 時空星獸, or Shi Kong Xing Shou.” says Sanqui “This is an unlicensed Chinese mongame for the Game Boy Color. In fact, I started a translation patch at one point, but I had trouble finding a translator willing to help, so I put it on hold.” while Andwhyisit and Kmeisthax would like to see the original Popolocrois titles for PlayStation and PlayStation 2, and an official translation of Mother 3 respectively. As for this writer, I’m still waiting to see English translations of the Bistro Recipe (known to most outside of Japan as Fighting Foodons) Game Boy and Game Boy Color games, I’m sure someone somewhere is working on them, and if not I can at least dream.

Improving Game Preservation

Although Smilesoft as a company and Telefang as an IP no longer exist, individuals like those featured here are doing their part to prevent more obscure titles from becoming lost media. A recent and common opinion seen is that as a society we could use plenty of improvement when it comes to video game preservation. When asked for how this can be done, obskyr says the best way is to “Patronize and donate to existing preservationist efforts like the Internet Archive and The Cutting Room Floor! In your off time, you can (and should!) be vocal about wanting re-releases, transparency, and information from video game companies.” and is hopeful that, “In the future, perhaps companies like Nintendo will work together with video game preservationists.” while the others took on a different angle, with Sanqui specifically stating, “Nintendo is great and all, but everybody cares about Nintendo. Nintendo games are going to be well preserved, so don’t worry about them! What about multiplayer games that no longer have functional servers? What about about Flash games, now that we’re all happy Flash is gone from browsers? What about Java games for old phones, the ones you saw advertised in old magazines? What about the games made on old 8-bit microcomputers, only spread on a few floppies among friends? Pay attention to the things nobody pays attention to. Telefang is one hidden gem, a quirky game with an interesting history and a passionate community today. What are the video game gems you know? ”, Kmeisthax mentions this point as well claiming, “The thing is, game preservation is a bit of a misnomer. Most games are objects of mass culture and produced in minimum quantities of 10,000 or more. The only part of console games in need of preservation are the hardware and source code, the latter of which we don’t get access to without reverse engineering. Other kinds of games, like Flash games or MMOs, are at far greater concern than Nintendo ROMs. What people want isn’t just game preservation, they want these games to remain legally accessible!” and Andwhyisit provided another point of view, “There are no easy answers,” clarifying that, “On one hand preserving those games for future generations is incredibly important, especially with Nintendo’s recent shutting down of digital platforms. On the other hand I feel like that preservation effort is being exploited by pirates who just want their free games.”

A Mongame Resurgence?

Besides translating, as you may be able to infer, this community is also very passionate about ‘mongames’ in general in addition to Telefang, and had plenty to say when I mentioned that it seemed as if mongames besides Pokémon are starting to make a comeback. In the past few years, in addition to ongoing series such as Yo-Kai Watch, Digimon Story, and Dragon Quest Monsters, we’ve seen upcoming indie titles such as Ooblets, the aforementioned Monster Crown, RE: Legend, and others start development and have fully funded Kickstarter campaigns in just a few days.

“The so-called ‘mongame’ genre has been around for a long time, as Telefang and many other games show, but it has always had to fight for legitimacy, being ever compared to the behemoth that is Pokémon.” says Sanqui, “This is not a unusual situation among video games. There was a time when first person shooters were labelled ‘Doom clones’, and a certain genre even bears the name of its first game to this day: roguelikes.The difference is the massive popularity the Pokémon franchise holds to this day. I don’t expect the popularity of Pokémon to dwindle any time soon, so mongames may, for a while, stay a niche for those who are interested in a bit more, but I do hope these games gain more appreciation.” Andwhyisit agrees and adds, “I feel like non-Pokémon mongames have always had niche appeal. However I’m sure that many people have realized that there are certain things that Pokémon series cannot give them, and game companies have realised that mongames other than Pokémon are making money outside of Japan. Indie developers have likely caught on that the west is starting to warm up to non-Pokémon mongames and are making those games that they have always dreamed of making”

“So I’d like to dispel the myth that non-Pokémon mongames aren’t really popular.” says Kmeisthax, “Yo-Kai Watch is already pretty big, especially in Japan. Genius Sonority (who worked on Pokémon Colosseum and Pokémon XD for the GameCube) also put out a handful of fairly successful mongames based around Wi-Fi signals called The Denpa Men. Looking further back, Monster Rancher was big enough to get an anime, at least. I’m deliberately ignoring Digimon here, because it’s a line of Tamagotchi with battle mechanics, but I guess it’s also had some mongame spin offs on consoles. Dragon Quest also jumped on the mongame bandwagon with some success.” Which as I’ve said in previous articles, expanded on mechanics from Dragon Quest V, which released four years before Pokémon. “Indie developers are heavily informed by their childhood gaming experiences, so we tended to get a lot of platformers with NES-style retrosploitation visuals. I guess the Pokémon kids are old enough to make games professionally now, so here’s to hoping that these games catch on too.”

“They’re finally breaking into the indie scene in a big way!” obskyr exclaims, “It’s a new wave of capable monster collection games, this time not by imitators or even big companies at all, but by fans of the genre. People are realizing they too can make something full-fledged and, perhaps more importantly, innovative. I feel like it’s more of a new dynamic entirely than a “resurgence”. These aren’t your grandma’s mongames.” Rachel adds “There definitely seems to be a lot of demand for “Pokémon-like games that aren’t Pokémon“, as they are so often described, and it’ll be interesting to see if the genre is finally able to break away into its own thing entirely with so many promising titles on the horizon.”

So in the end, the Telefang duology may have not gained the appreciation it deserved at launch, but over time a couple of curious individuals managed to learn about it, find all the information they could and develop an English translation and wiki site so it can continue to live on. As for all of the upcoming mongames, I would hope that they would learn and take inspiration from Telefang and other predecessors besides and as well as Pokémon.

I’d like to thank all who participated in the making of this piece and a special thanks to Rachel for providing high resolution images from Comic BomBom. An additional special thanks to Camden Jones of Game Informer for inspiring this piece.